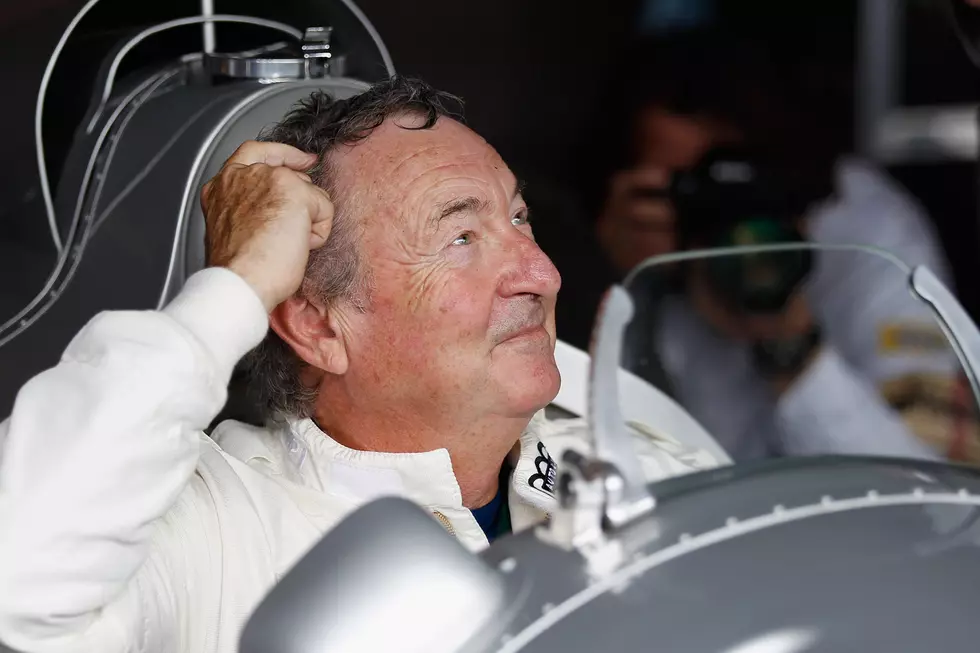

When Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason Entered a Le Mans Motor Race

Long before he became Pink Floyd's drummer, Nick Mason wanted to be a racing driver, and he always had one particular race in mind: the 24 Hours of Le Mans endurance contest.

Held annually since 1923 in France, it’s one of the oldest races still taking place, and it’s often regarded as the most prestigious. Any driver who wants to hold the Triple Crown of motor racing must win the Indianapolis 500, the Monaco Grand Prix and Le Mans.

Mason’s dream was inspired by his father, a filmmaker and also a racer who made a documentary about the sport. “Since I was a schoolboy, my ambition was to race at Le Mans,” Mason told RobbReport. “Doing so was definitely a bucket-list experience, but admittedly my bucket was much smaller then. I didn’t aspire to cross the Atlantic in a small boat or climb Mount Everest.”

He started racing six years earlier, after buying a pre-war Aston Martin Ulster. Mentor Derek Edwards, Mason later said, “taught me how to fettle the car and showed me the basics of cornering and cooking a full English breakfast – on top of a petrol tank!”

At this point, the rest of Pink Floyd continued to suffer over the creation of The Wall – a difficult time that would lead to the firing of keyboardist Rick Wright and the eventual departure of Roger Waters. Meanwhile, Mason was preparing to drive a Lola T297 prototype car, which would be piloted in turns by his Dorset Racing Associates teammates Brian Joscelyne, Tony Birchenhough and Richard Jenvey.

“I was lucky enough to be introduced to a really wonderful team that was amateur in status but entirely professional in approach,” he recalled. “All of the members were enormously helpful, and they made it clear that I was there to contribute to the cause.”

One element of that support was advice about facing the front while racing. “I'd been warned about it,” Mason told ESPN. “I made the mistake of trying to turn my head and look behind me on a straight going 200 mph. The wind got around my helmet and turned it around. I was driving blind for a bit.”

However, he wasn’t too concerned about the notion of an accident that might end his drumming career. “Life is dangerous,” Mason observed. “I think I'm a fairly cautious racer. One of the thing about sports that have a danger element about them is they're safe. You can't live your life thinking about not doing something because you couldn't do something else.”

On June 9, 1979, 55 cars set off on a track consisting of closed public roads and a racing circuit. Along with the aim of having their vehicles endure for the full 24 hours, the drivers faced heavy rain as they took turns with the wheel.

“Things were shared equally between the partners of the team,” Mason said. “I probably drove about seven hours of the 24, amounting to well over 500 miles. From that I learned just why Le Mans is one of the toughest races and how it proves the mettle of a car and a driver. Surprisingly, as an amateur you can receive an enormous amount of support from the professionals.”

The Dorset Racing Association’s Lola came 18th overall, completing 260 laps at an average speed of 111 miles per hour. That was enough for the car to come second in its class and for Mason to finish tops in the index of performance. A total of 25 cars – less than half the number that started – managed to complete the race, of which the last three failed to complete the necessary distance for a qualified finish. Coincidentally, Pink Floyd manager Steve O’Rourke, a fellow racing nut, also drove in his first Le Mans that year and came in 12th in a Ferrari. Movie star Paul Newman’s Porsche came in second.

Despite the temporary blindness and the rain, Mason enjoyed the experience so much that he went back four more times until 1984, though he admitted he enjoyed “an ever-increasing lack of success.” The upside was much greater, however. “That’s the great thing about Le Mans: It’s the last area in motorsports where an amateur can be competitive against the pros,” he said.

“You’re not expecting to beat them, of course, but you do have a chance because the race is so hard on the cars. It’s the equivalent of completing 12 consecutive grand prix races, and not at dissimilar speeds. Luck does play a part in the outcome. Racing at Le Mans was a great confidence builder for me, and it added credibility to my pursuits in motorsports. It didn’t matter where I finished; just participating showed commitment and proved I was serious about it. I also had the chance to become friends with motorsports superstars who I never would have met otherwise. If you get to that privileged position, you learn so much. You get to listen to your heroes tell you all the things that you might want to know.”

Mason eventually came to own more than 30 cars, including the Lola, all kept in an aircraft hanger in a “secret location” in England. He’s also written books about racing. Mason's daughter is married to professional driver Marino Franchitti, brother of retired IndyCar champion Dario; his second wife, Annette, would often co-pilot when he entered races. Mason has been a major contributor to the U.K.’s Goodwood Festival of Speed – an annual celebration of motor racing history – since its inception in 1993.

When he was once asked which Pink Floyd album he’d listen to while racing, Mason replied, “First of all, I can't think of anything more distracting than having music playing while racing. … It's sort of a mad question. It's like what would you like to eat while racing.”

He noted that driving a sports car and playing live were “very different. Without a doubt, auto racing is more dangerous," Mason said. "But in my case, music is far better paid.” Asked about his advice for people who wanted to follow his Le Mans lead, he said, “There’s almost certainly a Porsche or a Ferrari that you could get into now, but you need to be either rich or quick. Being both would be ideal.”

Pink Floyd Albums Ranked

More From WRKI and WINE